The application of ultrasound is keeping facilities cleaner longer, saving SWU time and money.

One way to set up a municipal water utility is to treat water at the intake and then run it through open basins for conditioning and ultimately filtration. There’s a routine with keeping such installations clean. Biofilms tend to grow on basin walls, then peel off in sheets that gum up the filters – cleaning them is a perpetual chore. Some of the biofilm settles to the basin bottom with other matter and the sediments have to be removed every month or so. That’s the setup that Searcy Water Utilities has in Searcy, Arkansas. And just like similar water utilities, SWU contends with biofilm growth. Several years ago, Scotty Boggs, then the water plant manager at SWU, was attending a conference on water quality when he passed the booth of a company touting the use of ultrasound to restrict the growth of biofilms and kill

toxic algae.

Granted, WaterIQ Technologies, was talking about keeping reservoirs and clarifiers clean, but could it be used by a water utility? Boggs stopped into the WaterIQ Technologies booth. The company was curious about Searcy’s use case and eager to help.

Boggs decided to test the ultrasound technology in two of SWU’s 11 basins, and it worked just as well as he or the company could have hoped. After initial experiments demonstrated that biofilm growth was significantly reduced and proved that SWU would have to clean its facilities far less often, the utility ordered equipment for all of its water basins. SWU continues to use ultrasound to help provide clean, safe drinking water today.

SWU operations and the problem with biofilm

Searcy Water Utilities, which serves several communities in northern Arkansas, draws its water from the Little Red River. SWU treats roughly 20 million gallons of water a day. After intake, the utility pulls minerals out, adjusts the pH, and treats the water with chemicals. After the water is treated, it is directed into SWU’s 11 basins, where the water is gently churned to blend in the chemicals, and where particulates are induced to settle.

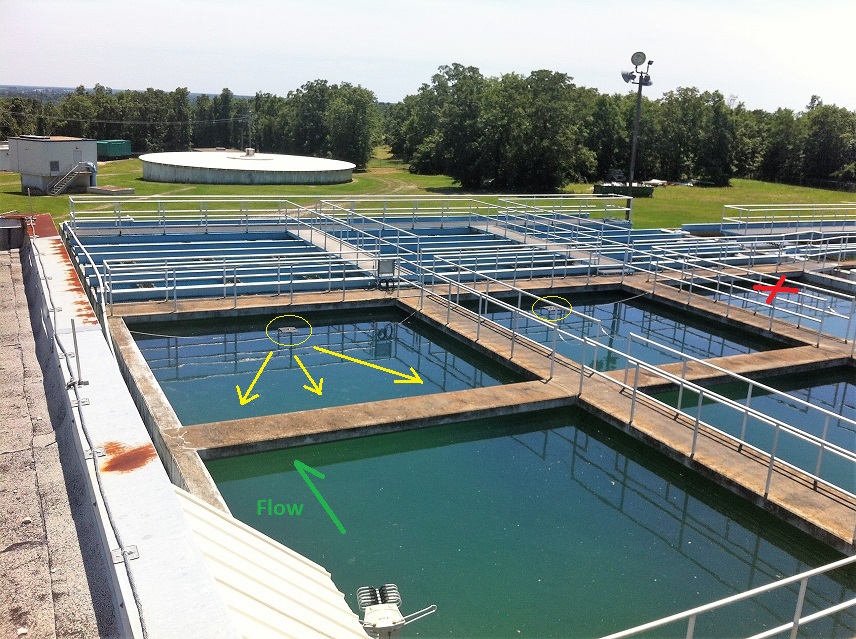

The water flows continuously through the basins, most of them roughly 24 feet wide, 100 feet long, and 14 feet deep. At the far end of every basin is a baffle wall and a series of small weirs that together represent the last stage of filtration before the water is distributed to customers.

Biofilms always grow on the basin walls, but growth gets vigorous in the summer as water warms and is exposed to longer hours of plant-nurturing sunlight. As the biofilms grow, patches of the stuff inevitably peel off the walls. Some of it sinks, adding to the build-up of sediment that must be periodically removed.

Much of the biofilm ends up floating to the baffle walls, however, where it impedes filtration. It was Scotty Boggs’ job to deal with the biofilm. “It looks like brown lily pads,” he said. “It might even get through and block off the weirs. The concern is that some of the organics could even get out.”

Traditionally a water utility has two choices for dealing with biofilms: either increase the frequency of cleanup operations or apply even more chemicals.

Boggs likes to keep chemical use to a minimum. Meanwhile, clean-ups entail shutting down basins, diverting utility staff, and diminishing the amount of water available for customers.

That’s why the proposition of a third option – using ultrasound technology – was intriguing. Boggs set up a three-basin experiment. He equipped two of his 11 basins with ultrasound devices and designated a third as a control. It was simple to set up, he said. “We could install it ourselves. There was nothing else to add.”

“We started in 2016 and ran the experiment through the summer,” Boggs continued. “After several months during the summer, the two basins had less material than the control. We ran it again in 2017 and 2018 and confirmed that the technology was successful enough to pursue in all our basins.”

It just so happened that in 2018 a new ultrasound unit was introduced with a wider range of frequencies, which enabled more effective targeting of biofilms and algae. The new version was also more power efficient.

“We procured 11 of them, and replaced our two earlier units,” Boggs said.

Before installing the ultrasound devices, in the summer months, SWU might have to shut down a basin once every 30 days or so to scour the basin walls. With ultrasound, even in the summer, SWU can let a basin operate for up to two months before having to clean its walls.

“From an operator’s standpoint, nothing can touch it,” Boggs said. “It’s not chemical. There’s no residual product to test. It’s not a continual cost. There are no maintenance issues. We just plug it in and forget it. It’s easy to do. The [Arkansas state] health department looked at it and thought it was just a neat technology.

“It worked out pretty good for us,” Boggs said.

[Scotty Boggs is now Assistant General Manager at Searcy Board of Public Utilities.]